The original books of the Bible were written in Hebrew (the Old Testament) and Greek (the New Testament). Parts of the books of Daniel and the Gospel of Matthew might have been originally written in Aramaic.

The original books of the Bible were written in Hebrew (the Old Testament) and Greek (the New Testament). Parts of the books of Daniel and the Gospel of Matthew might have been originally written in Aramaic.

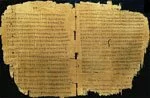

Many translations have been made over the years. In the early days of Christianity the Hebrew Old Testament was usually read in a Greek translation (the so-called Septuagint). As the church spread, the need for translations grew, taking the sacred text into widely accepted languages as well as local tongues. The Bible was soon translated into Latin (the language of the Roman Empire), Syriac (an Eastern Aramaic language), Coptic (Egyptian), and Arabic. By 500 AD, some estimate, scripture could already be found in more than 500 languages.

Unfortunately, translations were not always accurate and errors were made. For this reason – and also because they did not want “ordinary” people to be able to read the Bible – the (Roman) Catholic Church banned any further translations and used only a particular Latin text known as the Vulgate, which had been translated from the Greek around 600 AD.

In the 1380s the first English translations were made by John Wycliffe. By 1455 the printing press was invented (Gutenberg), and mass-production capabilities made additional English versions and other language translations more readily available.

Hundreds of translations into English (estimated around 450) have been made over the years. Some of the best known are: the King James (KJV, 1611), the New International Version (NIV, 1978), the New King James (NKJV, 1982), the New American Standard Bible (NASB, 1971) and the English Standard Version (ESV, 2001). This large number of translations is usually grouped into three main categories:

1) Literal translations: These translate the original texts word for word into the best English equivalent words. These translations are sometimes also referred to as interlinear translations, placing the English rendering along side the original Hebrew and Greek. Although they are undoubtedly the most accurate translations, they can be difficult to read because the flow of language follows the original Hebrew and Greek, quite different from modern English. The NASB as well as the ESV are good examples of literal translations.

2) Dynamic equivalent translations: These translations attempt to be as literal as possible, but restructure sentences and grammar from the original language to English. They attempt to capture thought and intent of what writers wanted to say. As a result, these are more readable in English, but have a higher degree of subjective interpretation than the literal translations. These translations include the KJV, NKJV, and NIV.

3) Contemporary language translations: These translation paraphrase the thought and intent of the original text into contemporary English. The result is easy to read, but the text is largely a subjective interpretation of the translator. These versions, such as the well known The Message and The New Living Translation, should be approached with great care. Use them perhaps for supplementary readings, but be aware that these texts can (and often do) differ significantly from the original Bible texts.

Every translation requires interpretation. Why? Because languages do not translate one on one. That is, not every word has a unique word to match it in the other language. Also some tongues are richer in expression than English (such as Greek) or smaller in vocabulary (such as Hebrew). A translator must interpret the original meaning and find an equivalent wording, but this makes the result subject to the biases of the translator. Bottom line: interpretations differ and errors can occur. When translations differ significantly, research into the original language can help clarify the message.

To complicate things a bit, a small number of NT verses are not supported by all ancient manuscripts; this forces translators to decide which verses to incorporate. Most translators are cautious to err on the safe side and note for the reader any verse not supported by the majority of manuscripts.

As an illustration, let’s look at the Lord’s Prayer from Matthew 6:9-13 in the New International Version and the King James Version:

The Lord’s prayer in the King James:

“After this manner therefore pray ye: ‘Our Father which art in heaven, Hallowed be thy name. Thy kingdom come. Thy will be done in earth, as it is in heaven. Give us this day our daily bread. And forgive us our debts, as we forgive our debtors. And lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil: For thine is the kingdom, and the power, and the glory, for ever. Amen.’”

Now read the Lord’s prayer in the NIV:

“This, then, is how you should pray: ‘Our Father in heaven, hallowed be your name, your kingdom come, your will be done on earth as it is in heaven. Give us today our daily bread. Forgive us our debts, as we also have forgiven our debtors. And lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from the evil one.’

Apart from “old” English versus more modern English style, notice the two differences in the last verse:

1) “The evil one” versus “evil.” The KJV asks for deliverance from “evil” while the NIV asks to deliver us from “the evil one.” There is no little theological difference between the two. The original Greek text actually uses an adjective with an article, making “the evil one” the only correct translation. We pray to be delivered from the evil one, not from any danger, disaster, or from the general ugliness of the world.

2) An extra sentence. Compared to the NIV, the KJV has an extra sentence at the end: “For thine is the kingdom, and the power, and the glory, for ever, Amen.” This is a good illustration of a later addition to the oldest preserved Greek manuscripts. As the NIV mentions in a footnote: “some late manuscripts: for yours is the kingdom and the power and the glory forever. Amen.” Other verses in the NT have similar additions. None of these are of vital theological consequence, but it is important to be aware of these variations.

Therefore the differences between the various English translations are not the result of differences in the extant (still in existence) ancient manuscripts, but merely the result of choices (and sometimes errors) made by the translators during the translation to English.

By: Windmill Ministries